William J. Winslade

SPECIAL SECTION: PSYCHOANALYSIS AND FREE SPEECH

William J. Winslade

William J. Winslade Ph.D., J.D., is James Wade Rockwell Professor of Philosophy in Medicine, University of Texas, Galveston; visiting law professor, University of Houston; adjunct philosophy professor, University of Texas and licensed research psychoanalyst in California.

William J. Winslade

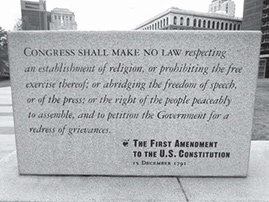

In many authoritarian countries, critics of the prevailing governments risk reprisals, such as harassment, arrest, imprisonment or even assassination or execution. In the United States there is a long tradition of protection of free speech embodied in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Founding Fathers believed that free expression, including conflicting points of view, would create better policies when good ideas could flow freely and drive out bad or even foolish ones. Critics of government were to be expected and their arguments and objections were to be taken seriously and properly evaluated.

Over the years, however, the right to free speech has expanded exponentially. The explosion of communication technologies from newspapers to radios to television to computers to the Internet and its many spin-offs like Twitter, Instagram and others, provide unprecedented opportunities for the expression of ideas of all kinds—not just political ideas and critiques. Many types of advocacy for controversial, unpopular and radical ideas are freely expressed and widely disseminated. We are constantly bombarded by multiple media sources spewing political rhetoric and critical commentaries under the protection of free speech.

Unlike philosophy or litigation in which speech is typically presented publicly, free association is communicated in a private and confidential setting.

Although the freedom from reprisal for expressing controversial ideas is a hallmark of an open society, unfettered free speech creates significant problems. One is the problem of determining relevant facts and criteria for evaluating the truth and the worth of media hype. Much free speech is merely an expression of unverified claims or unsupported opinions. The free market ideas frequently lack any quality control. As a result, free speech in America often creates a cacophony of inflated claims about politics, religion, education, business and many other topics. Exaggerated advertisements for all kinds of goods and services are relentlessly promoted on television and by telephone solicitation. This may also be why Ponzi schemes dupe greedy investors. Vulnerable people purchase bogus bargains and gullible people believe convincingly conveyed false and sometimes outlandish offers.

In addition, fervent advocacy and unchecked overstatement fuel prejudice about many political topics. Although this type of free speech provides entertaining material for humorists like Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, they utilize heavily edited clips to poke fun at politicians, Fox News and other targets. But this does not prevent seemingly endless streams of free speech unsupported by reliable evidence and sound reasoning.

Few remedies are available to curtail the torrents of phony, frivolous and misleading free speech. Fact checkers can report false claims but they cannot prevent the proliferation of factual errors. Education at all levels should emphasize the importance of precision, accuracy and evidence-based speech. It is important not to accept truth claims at face value. One should always evaluate the evidence and arguments on the basis of these claims.

In this article, I will discuss three types of free speech—philosophical discourse, adversary litigation and psychoanalytic therapy, which are supported by distinct and different rules of evidence and acceptability, and will explain why these are governed by different criteria.

PHILOSOPHICAL DISCOURSE

Philosophers often spend considerable time discussing what is real (ontology), what is known and knowable (epistemology), and what is right conduct (ethics). In philosophical discourse concepts and theories are examined to determine if they are clear, coherent and based on sound reasoning. Philosophy is not merely a matter of beliefs or opinions. Philosophers typically submit their ideas to colleagues to test the reliability of the evidence and arguments presented. Philosophical discourse that fails to meet these standards is rejected in favor of concepts and theories backed by better evidence and more rigorous reasoning.

ADVERSARIAL LITIGATION

Speech must meet specific standards of acceptability in litigation in the adversary system of justice. The adversary system is based on the assumption that every litigant in a civil or criminal trial before a judge or jury will follow rules of evidence and procedure for presenting their case for their client. It is presumed that the best evidence and legal arguments will prevail. The judge or jury has the responsibility to make a fair decision, not on the basis of their personal opinions or beliefs, but rather on the applicable legal rules and the persuasiveness of the evidence and arguments the attorneys present. As a further test of reliability, the appellate courts provide an opportunity to review the strength and weight of the evidence as well as arguments presented at the trial.

PSYCHOANALYTIC SPEECH

In psychoanalysis the technique of free association on the surface may seem to resemble unfettered free speech. The analysand is supposed to say anything that comes to his or her mind. Unlike philosophy or litigation in which speech is typically presented publicly, free association is communicated in a private and confidential setting. Although a person is encouraged to say whatever comes to mind, the beliefs or opinions expressed are not evaluated by external evidence or rational argument. The speech provides an opportunity for the analyst and the analysand to work together to discern underlying feelings, emotions and patterns of thought. The analyst listens to the analysand’s free associations, incidental remarks, dreams and reports of events or encounters, not for the purpose of assessing truth or logic but to gain insights about the psychological life of the analysand. Of course, free associations become restricted by defenses such as denial and repression. The analysand and the analyst must make a joint effort to try to understand not only what is being said but also what is not being said. Indeed, the analyst must “listen with a third ear” to what has not been said. The challenge for the analyst is not to take the free associations at face value. Analysands must also not assume their free associations tell the whole story about their emotional life. The analysand seeks insights and self-knowledge while the analyst seeks understanding of the meaning of the emotions and experiences in the analysand’s life and relationships. The analyst seeks clues revealed from the overt as well as the hidden emotions that emerge from the conversations between the analyst and the analysand. Different from speech in philosophy or litigation, free association initiates a special type of collaborative exploration between analyst and analysand to gain a better understanding of the emotional life of the analysand.

It is no surprise many people feel bombarded by unfettered free speech and do not know how to assess the reliability of what they hear or see on television, the Internet or from other unregulated sources. They are not sure what to believe or what to take seriously. In the three types of free speech I have claimed are different, there are rules of evidence and acceptability. Even when disagreements arise, there are accepted means to resolve them. It is critical in an open society to challenge claims that are not supported by good evidence or sound reasoning. Speech in philosophy, litigation and psychoanalysis are assessed in terms of worthy human goals and aspirations. A flourishing open society requires policies and practices that evolve from good evidence and sound reasoning.