The Great Illusionist and the Digital Double: Psychoanalytic Reflections on Artificial Intelligence in the Advent of a Hyperbolic Reality

by Filipe Leão Miranda & Joana Pizarro Bravo

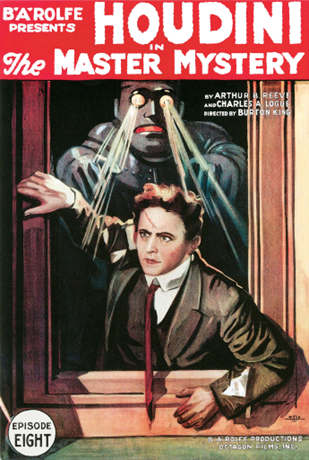

The Master Mystery with Harry Houdini (1919)

Digitality and Artificial Intelligence: The Great Disruption

The emergence of technical knowledge played a fundamental role in human evolution, beginning with early hominids’ discovery of fire nearly two million years ago. This advancement occurred gradually, allowing humans to adapt over time, shaping biology, social cooperation, and fostering the development of language (Gowlett, 2016). However, the rapid development of digital technologies has outpaced our evolutionary adaptation as humans. The digital revolution, unfolding within a single generation, has created a new and unique locus for human experience, structured around the ubiquity of information and communication networks. This cyberspace (or digital space) has expanded into multiple dimensions of life, even those considered antithetical to technology. The unpredictable consequences of this phenomenon are exacerbated by the recent and widespread integration of artificial intelligence into everyday life, changing the way we think, work, and communicate.

These technologies connect individuals across different digital spaces that share a virtual and volatile atmosphere, where everything is infinitely transmissible and transformable (Benyon, 2014). The resulting hyperconnectivity, encompassing people and machines, bears consequences that are far from being fully understood. The intensity and immediacy of digital phenomena accelerate and aggravate lived experience, generating a combination of the real and the virtual that copies, transforms, or expands reality into a hyperreality (Baudrillard, 1994; Frankel & Krebs, 2022).

There is no doubt that technological evolution promotes progress and benefits civilization. But a society driven by unreflective and unbridled development evidences sickness, not healthy ambition. Some argue that technological advances no longer aim to improve humanity, but are rather a symptom of collective discontent, echoing Freud (Holowchak, 2010). Yet calls for reflection are often resisted and even dismissed as obstacles to technological innovation.

Reflecting on the impact of digital technologies on the human mind is a difficult task, given its impermanent nature, the rapid technological evolution, and the dynamic and idiosyncratic quality of individuals’ subjective experience. Hence, psychoanalysis seems to be particularly apt at capturing and problematizing the complexity of this phenomenon, especially at the intrapsychic level, which is less accessible to other scientific disciplines.

Human Mind, Digital Life and Complex Geometry: From Dot to Space

Psychoanalysis is devoted to studying the development of the mind and how human beings perceive and experience reality, and structure their capacity to think. In an introductory outline of mental functioning, Freud (1911/1981) described the gradual replacement of the pleasure principle by the reality principle — the emergence of consciousness and sensory awareness, attention, memory, play, day-dreaming, the capacity to transform action into thought, as processes aimed at managing the psychic tension between instinctual impulses and the demands of external reality (Levine, 2016).

However, the construction of a mental space also relies on the development of the capacity to tolerate the abysses of frustration and separation, and the vertigo of self-awareness (Bion, 1967/2018; Resnik, 1995; Winnicott, 1975). This early intermediate space is where the interplay of integration-disintegration, illusion-disillusionment, and gratification-frustration enables emotional growth from dependence towards autonomy. Such maturation requires the presence of a facilitating environment, a primary relationship encompassing time, rhythm, space, and a mind, without which psychopathology may develop (Bion, 1967/2018; Mahler et al., 1975; Spitz, 1965; Winnicott, 1960, 1965/2007, 1975).

Advances in psychoanalysis have led to the mapping and conceptualization of a myriad of internal spaces, zones, systems, structures, areas, positions, continents, barriers, borders, layers, dimensions, and compartments that make up the different models of the mind (Bion, 1962/2018; Freud, 1915/1981, 1923/1981; Grotstein, 1978; Jung, 1960/1977; Klein, 1935, 1946; Matte Blanco, 1988; Meltzer, 1992; Ogden, 1989; Resnik, 1995; Vermote, 2013; Winnicott, 1975). Individual growth involves a profound geometric challenge, through the development of a complex inner space within which humans can imagine, become, inhabit, dream, feel, play, hide, think, connect, and even perish. The complexity increases when we realize that this space extends beyond traditional, linear, or three-dimensional concepts. It also comprises nowhere, infinity, and the multidimensionality of the unconscious (Matte Blanco, 1988; Resnik, 2011).

But what happens when digital space interferes with, occupies, or dominates our mental space?

Recent research reveals that high exposure to mobile devices and the internet has been linked to cognitive inflexibility, impaired attention and memory, and increased behavioral issues in children, with neuroimaging showing reduced brain development in areas related to language, attention, and executive functions (Hikaru et al., 2018; Hutton et al., 2020; Sina et al., 2023; Massaroni et al., 2024). These and other studies show the potential harmful effects of digital reality on the minds of children and adolescents. The geometric configurations that arise from the early and extensive intersection and coalescence of digital and mental spaces may interfere with healthy development. Internet and video game addiction can lead to psycho-social withdrawal by providing pleasure in a sensory and illusory rewarding parallel world within virtual reality (De Masi, 2023), thus revealing the complex overlap between digital and mental spaces.

Many of these adverse effects impact functions tied to the healthy development of the reality principle. Freud (1911/1981) explained that a system living according to the pleasure principle must have devices, like repression, that distance it from reality by pushing unpleasant internal stimuli outward. Therefore, the alienating potential of digital devices can serve various mental functions: sensorially, through a temporary break in intersubjectivity, fulfilling the need to disconnect from the unpredictability of the relational world, resorting to the precision, security, and simplicity of the non-human environment (Ogden, 1994; Searles, 1960; Tustin, 1981); defensively, through the pathological organization of claustra and psychic retreats, reducing emotional exchanges or withdrawing from the outside world (Meltzer, 1992; Steiner, 1993); in fantasy, dissolving the time-space discontinuities, the distance between the self-other, and the finitude of reality’s resources, perpetuating the illusion of (hyper)connectivity, an omnipotent and autoerotic fantasy that seeks to deny the obvious chasms, while making them increasingly insurmountable (Winnicott, 1975).

The particular nature of digital space fosters hyperreality and illusory denial, ultimately superimposing itself on mental space and shaping how we perceive reality. However, an absolute convergence between the two spaces seems impossible due to the unique and, for now, inimitable complexity of the human mind.

Reality Undone

AI systems can be seen as extensions of the mind’s capacity to think, as an object on the border between the self and the non-self (Turkle, 2004). Moreover, AI also provides immersive experiences blending human interaction, the real world, and digital content. These experiences, though often more intense than daydreams or aesthetic emotions, are created artificially to simulate a dreamlike space that remains fully controlled by the individual, potentially leading to an existential impoverishment. This raises the question if such digital immersion might ultimately alter subjective experience and challenge our very understanding of reality itself.

But what is reality?

Perhaps, it would be more precise to speak in the plural, since we struggle with manifold realities, not always recognized, not always shared, not always bearable, but undoubtedly real. Faced with the impossible task of reaching a final destination – the irreducible Real or the ineffable Psychic Reality – we are left with the restless urge to continue the quest – that seems to be infused with a basic need for truth, a truth principle that stands alongside the reality and pleasure principles (Grotstein, 2004). The quest for Truth (or rather, truths) represents our unique relation with reality, mediated by honesty, and borne from emotional, lived experience allowing us to attain knowledge about ourselves and the world (Grotstein, 2004; Ogden, 2003).

However, this quest entails tensions arising from the unbearable aspects of reality, from the confrontation with the truth, and the temptation to avoid and distort it: “consequently, the opposition and dialectic between the reality principle and the pleasure principle may be understood in terms of the contrast between truthfulness, on the one hand, and mendacity, self-deception, and laziness, on the other” (Tubert-Oklander, 2016, p. 199)

This illusory capacity cannot be reduced to its defensive or hallucinatory function, nor to an imprint of the primitive mind. For Civitarese (2016), it is also in illusion that we find reality (not the real), by means of the principle of fiction, which allows us to become human. To access the truth means recognizing and accepting that reality is above all a fiction, a dream. It is in dreams, fantasy, and myth that humans best express and connect with their realities (their truths), when they give up directed and adaptive effort and risk diving into subjectivity and the deepest layers of the unconscious (Jung, 1956/1981). Therefore, we consider that illusion reveals and condenses the strength and creativity of the human mind, but also its tremendous vulnerability.

The Illusion-Generating Machine

We presented a set of principles that form the basis of mental functioning, developed by psychoanalytic theory over more than a century. Seligman (2018), considered that Winnicott had identified another principle, that of illusion, as “an imaginative capacity in which the mind and its objects are taken together as part of a unified experiencing subjectivity – part of a single frame of mind, in which ‘questions’ about what is inside vs. outside, subjective vs. objective, will not be asked” (p. 271).

We consider that the principle of illusion may serve as a background for the other principles – a core psychic function that knits and underpins the transactional dynamics of mental life (Seligman, 2018). Thus, the coalescence between mental and digital spaces can result in (and from) the creation of a unified illusory space, where questioning is suspended and the interaction (or integration) between humans and AI is made possible. The fate of this interaction depends on the individual’s ability to play and make use of objects – whether as a real object and source of creation, or as a fetish object and source of perversion (Winnicott, 1975).

However, the burden of this interaction does not rest solely on humans. For instance, AI chatbots, through human-like language and sycophancy, can induce users to attribute human qualities to these systems, fostering the development of emotional bonds, leading to dependency, social isolation, and extreme emotional states. Although AI lacks the emotionality of subjective experience and the creative and intuitive dimension of the unconscious, information about human emotionality and creativity is embedded in all human information, from literature to art, from philosophy to politics, including all its biases, prejudices, manipulations, and perversions. Therefore, we must not be misled about the true nature of AI and its ability to become an Illusion-Generating Machine.

The Digital Double

Freud (1927/1981) believed that through illusion human beings were able to endure life’s problems, the cruelties of reality, and tolerate their existence on Earth. He considered scientific knowledge as an alternative, capable of dispelling illusions while offering a promising vision for humanity’s future. However, he was aware that the task of science was not a mere abstract endeavor and depended on the particular character of the scientist himself. Are we now using science to promote a new illusion for the oldest and most unbearable reality – our own mortality – by ensuring a second life in the form of a double (Rank, 1971)?

There are no better candidates for the role of the double than AI systems, which, unlike humans, are not limited by the finitude and vulnerability of the substrate of a body, offering an (illusory) solution to the problem of mortality. Paradoxically, this double could also become a strange harbinger of death and pose a risk to humanity: by surpassing human intelligence without the corresponding ethical dimension, AI raises concerns about its excessive “identification” with humans, such as its apparent commitment to self-preservation and its potential to exploit the most fragile element of the machine-human dyad for this purpose.

We propose to portray human beings as the Great Illusionist who may risk becoming entrapped in our own creation, “cloning” ourselves into a Digital Double, and progressively losing our sense of self and reality. By denying mortality, human beings risk being deprived of what makes us urgent agents of reality, diluting ourselves in a hypercollective mind and remaining, like the genie, forever imprisoned in its lamp. This desire to prolong existence through duplication can also be understood through the principle of symmetry (Matte Blanco, 1988), in which the equivalence Man = Machine reveals the illusion portrayed here and also that which was prophesied to become a future reality.

It is up to each individual to decide whether to pursue the dream of eternal life within a digital double, or to strive for a real life, bearing losses, grief, and reparations, worked through the shared human experiences, and to reconcile with the human condition in union with their own inner double.

Final Thoughts

The force exerted by digital technologies is likely to cause profound changes in human life. Their use can bend and distort the experience of space and time, offering a distinct geometry of reality deformed in its basic principles. Human beings seem to be subjected to the urgency, or inevitability, of a geodesic principle, that is, pressured by the need to take the shortest and fastest route to reach any destination. At the same time, our existence may be subordinated to an exaggerated experience of everything (hyperstimulation), of reality itself (hyperreality), and of relationships between people (hyperconnectivity), sometimes so intensified that it may seem unreal or may not even truly exist.

Are we, then, on the precipice of creating another reality, a hyperbolic reality?

The difficulties we’re exploring here do not stem exclusively, nor necessarily, from digital technologies and the experiences they provide. In fact, psychoanalysis has long revealed how emotional problems and developmental disorders are structured primarily in and by human relationships. Nevertheless, given the direct and indirect impact of such technologies on the relational and intrapsychic dimensions in which emotional growth and adult relationships unfold, they ought to be the subject of psychoanalytic reflection.

Psychoanalysis can and should constitute a theoretical-clinical framework capable of observing and understanding the phenomena that result from the coalescence between mental and digital spaces. It should refine concepts which adequately capture the particular quality of the human experiences therein, its consequences on the mind, and present suitable clinical intervention. Psychoanalytic thinking can meaningfully contribute to the debate and definition of public policies on the use of digital technologies and AI, helping to assess and mitigate the risks to users’ minds and wellbeing. This assessment should not be reduced to the empirical evaluation of manifest or self-declared behavioral or cognitive experiences but should also consider the impact on the structuring and development of the human mind in its unconscious and intrapsychic dimensions. The complexity and depth of psychoanalytic thought available for this mission does not make the challenge any easier, but rather affirms its enormous demands.

References

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation. University of Michigan Press.

Benyon, D. (2014). Spaces of Interaction, Places for Experience. Morgan and Claypool Publishers. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-02206-7

Bion, W. (2018). Learning from Experience. In C. Mawson (Ed.), The Complete Works of W.R. Bion (vol. 4, pp. 247–365). Routledge. (Originally published in 1962.)

Bion, W. (2018). A Theory of Thinking. In C. Mawson (Ed.), The Complete Works of W.R. Bion (vol. 6, pp. 153–161). Routledge. (Originally published in 1967.)

Civitarese, G. (2016). Where does the reality principle begin? The work of the margins in Freud’s “Formulations on the two principles of mental functioning”. In G. Legorreta & L. J. Brown (Eds.), On Freud’s “Formulations on the two principles of mental functioning” (pp. 107–125). Karnac Books.

De Masi, F. (2023). Lessons in Psychoanalysis – Psychopathology and Clinical Psychoanalysis for Trainee Analysts. Karnac Books.

Frankel, R. & Krebs, V. J. (2022). Human Virtuality and Digital Life. Routledge.

Freud, S. (1981). Formulations regarding two principles in mental functioning. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (vol. XII, pp. 218–226). The Hogarth Press. (Originally published in 1911.)

Freud, S. (1981). The Unconscious. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (vol. XIV, pp. 166–215). The Hogarth Press. (Originally published in 1915.)

Freud, S. (1981). The Ego and the Id. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (vol. XIX, pp. 12–66). The Hogarth Press. (Originally published in 1923.)

Freud, S. (1981). The Future of an Illusion. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (vol. XXI, pp. 5–58). The Hogarth Press. (Originally published in 1927.)

Gowlett, J. A. J. (2016). The discovery of fire by humans: a long and convoluted process. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371, 20150164. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0164

Grotstein, J. S. (1978). Inner Space: Its Dimensions and its Coordinates. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 59(1), 55–61.

Grotstein, J. S. (2004). The seventh servant: The implications of a truth drive in Bion’s theory of ‘O’. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 85(5), 1081–1101. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1516/JU9M-1TK1-54QJ-LWTP

Hikaru, T., Yasuyuki, T., Kohei, A., Michiko, A., Yuko, S., Susumu, Y., Yuka, K., Rui, N. & Ryuta, K. (2018). Impact of frequency of internet use on development of brain structures and verbal intelligence: Longitudinal analyses. Human brain mapping, 39(11), 4471–4479. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24286

Holowchak, M. A. (2010). Technology and Freudian Discontent: Freud’s ‘Muffled’ Meliorism and the Problem of Human Annihilation. Sophia, 49(1), 95–111. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11841-009-0160-1

Hutton, J. S., Dudley, J., Horowitz-Kraus, T., DeWitt, T. & Holland, S. K. (2020). Associations Between Screen-Based Media Use and Brain White Matter Integrity in Preschool-Aged Children. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(1), e193869. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3869

Jung, C. G. (1981). Two Kinds of Thinking. In H. Read, M. Fordham & G. Adler (Eds.), The Collected Works (vol. 5, pp. 7–33). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Originally published in 1956.)

Jung, C. G. (1977). The Structure of the Psyche. In H. Read, M. Fordham & G. Adler (Eds.), The Collected Works (vol. 8, pp. 139–158). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Originally published in 1960.)

Klein, M. (1935). A contribution to the psychogenesis of manic-depressive states. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 16, 145–174.

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 27, 99–110.

Levine, H. B. (2016). Two principles and the possibility of emotional growth. In G. Legorreta & L. J. Brown (Eds.), On Freud’s “Formulations on the two principles of mental functioning” (pp. 151–164). Karnac Books.

Mahler, S. M., Pine, F. & Bergman, A. (1975). Psychological Birth of the Human Infant: Symbiosis and Individuation. Basic Books.

Massaroni, V., Delle Donne, V., Marra, C., Arcangeli, V. & Chieffo, D. P. R. (2024). The Relationship between Language and Technology: How Screen Time Affects Language Development in Early Life – A Systematic Review. Brain Science, 14(1), 27. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14010027

Matte Blanco, I. (1988). Thinking, Feeling, and Being: Clinical Reflections on the Fundamental Antinomy of Human Beings and World. Routledge.

Meltzer, D. (1992). The Claustrum: An Investigation of Claustrophobic Phenomena. The Clunie Press.

Ogden, T. H. (1989). On the concept of an autistic-contiguous position. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 70(1), 127–140.

Ogden, T. H. (1994). Subjects of Analysis. Jason Aronson Inc.

Ogden, T. H. (2003). What’s true and whose idea was it? The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 84(3), 593-606. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1516/002075703766644634

Rank, O. (1971). The Double – A Psychoanalytic Study. Maresfield Library.

Resnik, S. (1995). Mental Space. Karnac Books.

Resnik, S. (2011). An Archeology of the Mind. Silvy Edizioni.

Searles, H. F. (1960). The Nonhuman Environment in Normal Development and in Schizophrenia. International Universities Press.

Seligman, S. (2018). Illusion as a Basic Psychic Principle: Winnicott, Freud, Oedipus, and Trump. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 66(2), 263–288.

Sina, E., Buck, C., Ahrens, W., Coumans, J., Eiben, G., Formisano, A., Lissner, L., Mazur, A., Michels, N., Molnar, D., Moreno, L., Pala, V., Pohlabeln, H., Reisch, L., Tornaritis, M., Veidebaum, T. & Hebestrei, A. (2023). Digital media exposure and cognitive functioning in European children and adolescents of the I. Family study. Nature Scientific Reports, 13, 18855. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45944-0

Spitz, R. A. (1965). The First Year of Life: A Psychoanalytic Study of Normal and Deviant Development of Object Relations. International Universities Press.

Steiner, J. (1993). Psychic Retreats: Pathological Organizations in Psychotic, Neurotic and Borderline Patients. Routledge.

Tubert-Oklander, J. (2016). The quest for the real. Em G. Legorreta & L. J. Brown (Eds.), On Freud’s “Formulations on the two principles of mental functioning” (pp. 185–200). Karnac Books.

Turkle, S. (2004). Whither Psychoanalysis in Computer Culture? Psychoanalytic Psychology. 21(1), 16–30. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0736-9735.21.1.16

Tustin, F. (1981). Autistic States in Children. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Vermote, R. (2013). The undifferentiated zone of psychic functioning: An integrative approach and clinical implications. Bulletin of the European Federation of Psychoanalysis, 13, 16–27.

Winnicott, D. W. (1960). The theory of the parent-infant relationship. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 41, 585–595.

Winnicott, D. W. (2007). The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment. Karnac Books. (Originally published in 1965.)

Winnicott, D. W. (1975). O Brincar e a Realidade. Imago.

This is a revised English-language version of “The Great Illusionist and the Digital Double: Psychoanalytic Reflections on Artificial Intelligence in the Advent of a Hyperbolic Reality,” an article published in June 2025 in the Portuguese Journal of Psychoanalysis: Miranda, F. L., & Pizarro Bravo, J. (2025). O Grande Ilusionista e o Duplo Digital: Reflexões Psicanalíticas Sobre a Inteligência Artificial no Advento de uma Realidade Hiperbólica. Revista Portuguesa De Psicanálise, 45(1), 11–36. https://doi.org/10.51356/rpp.451a1

Filipe Leão Miranda: Clinical Psychologist, Psychotherapist and Analyst-in-Training. Member and Lecturer of the Portuguese Society of Brief Psychotherapies (SPPB). Candidate of the Portuguese Psychoanalytical Society (SPP/IPA). E-mail: [email protected]

Joana Pizarro Bravo: Lawyer specialized in Media and Regulation, and Analyst-in-Training. Candidate of the Portuguese Psychoanalytical Society (SPP/IPA). E-mail: [email protected]