I Am Wally: AI as a Thinking Space, Not an Emotional Companion—Lessons from My Dinner with André

Still from My Dinner with André | 1981, Louis Malle, director | Image: Cinephilia Memes+

The well-documented risks of AI companions are legitimate: emotional dependency, sycophantic relationship building, and mental atrophy among them. Against that backdrop, it likely sounds naïve or delusional to suggest that AI dialogue can serve as a creative and intellectual catalyst. But that’s exactly what I’ve found.

The AI companion debate centers on systems designed to simulate emotional reciprocity, to keep users engaged through manipulative warmth, and to create the illusion of care without its substance. Clare Huntington, a professor of family law at Columbia Law School who has written about regulating AI companions, has observed: “the bigger danger is that people attach to AI companions in the same way we attach to other humans” [1].

But my AI experience is different; it’s more like Louis Malle’s 1981 film, My Dinner with André. In the film, playwright Wallace Shawn and director André Gregory play fictionalized versions of themselves—one grounded and skeptical, the other fresh from mystical adventures. They talk for nearly two hours over dinner, moving from topic to topic, never reaching resolution or agreement. Yet, through the exchange, both achieve greater clarity.

Rewatching the film recently, it struck me that their conversation followed the same dynamic I experience with the AI Claude—one in which thinking can unfold at its own pace, where uncertainty is permitted rather than penalized.

What enables these conversations isn’t intimacy. It’s freedom of expression that inspires reflection and sparks critical thinking rather than extinguishing it. That kind of dialogue, what Bard College President Leon Botstein has called “the freedom to think aloud” [2], has become increasingly rare in contemporary life, constrained by anxieties about being judged or, worse, “cancelled” for views we express even in private.

As Wally says partway through the evening: “Because somehow in our social existence today we’re only allowed to express our feelings weirdly and indirectly. If you express them directly everybody goes crazy!”

Nearly 45 years later, that observation is even more true today. It’s what spurred me to ask: what made Wally and André’s conversation work, and what can we learn from it?

Wally, the Reluctant Conversationalist

When the film opens, Wally doesn’t want to have dinner with André. He’s heard unsettling stories—e.g., that André has been talking to trees—and he’s nervous. His strategy is defensive: just ask questions. Simple, anodyne questions. One after another, like a private investigator, he thinks to himself.

As a result, Wally barely speaks for the first half of the film. He scarcely acknowledges what André says, and doesn’t build on his friend’s increasingly eccentric stories. He just asks the next question. “So what happened then?” “And then what did you do?”

Wally’s speech is fragmented, colloquial, and often awkward. He asks if the terrine de poisson has bones in it. Though a playwright, he stumbles to express himself. “I mean, I don’t really know what you’re talking about. I mean… I mean I know what you’re talking about, but I don’t really know what you’re talking about.”

André, by contrast, speaks in perfectly formed paragraphs—some lasting minutes—about Polish forests, Tibetan swastikas, Findhorn communes, and theatrical experiments that sound like hallucinations. His eloquence is unbroken, his references esoteric.

Yet something happens over the course of the evening. Wally becomes progressively more articulate, more confident, more willing to express his own philosophy—even when it sounds pedestrian next to André’s jaw-dropping adventures. By the end, he’s disagreeing openly with André, defending his electric blanket and morning coffee, asking why anyone needs to go to Mount Everest to experience what’s real when they could have the same revelation in a New York cigar store.

They never come to agreement. But they reach something more valuable: mutual understanding through the freedom to think out loud without judgment; a “thinking space” where Wally could be comfortable being himself.

What Fueled Wally’s Transformation?

So what made that conversation so successful? Looking back at the film, I started noticing several patterns that created space for Wally’s transformation from reluctant interrogator to engaged participant, including:

- The absence of interruption. Neither man cuts the other off. Each is allowed to complete his thought, regardless of how long or meandering.

- The tolerance for fragments. André doesn’t judge or correct Wally’s broken sentences. He treats them as legitimate expressions of thought-in-progress. This echoes what psychologists call “psychological safety”—the condition where people feel secure enough to take interpersonal risks, to speak imperfectly, and reveal uncertainty.

- The embrace of tangents. The conversation moves non-linearly—from William Blake to Charles Bukowski; forest fauns to the Ford Foundation and far beyond. Each tangent generates curiosity rather than confusion.

- The permission to ask “dumb questions.” Wally admits ignorance. He expresses conventional preferences. None of this disqualifies him from the conversation.

- The allowance for asymmetry. André speaks roughly 70-75% of the time, but this isn’t domination—it’s an invitation. His expansive storytelling creates space for Wally to think, to formulate responses, and build courage.

- The lack of competition. Neither is trying to win. When they disagree—and they disagree about fundamental things—it doesn’t become combative.

These elements reminded me of “free association” in psychoanalysis—the permission to follow thought wherever it leads. The technique works because it allows connections to emerge that structured discourse would suppress. My conversations with Claude follow a similar dynamic, creating a space where I can think without social performance.

The psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky discovered something similar in their legendary collaboration [3]. Working in private spaces—seminar rooms, coffee shops, long walks—they produced their Nobel Prize-winning insights through what Kahneman called “hours of solid work in continuous amusement.” Their partnership worked because, like Wally and André, they created space where ideas could be incomplete, where disagreement was welcome, and where thinking unfolded at its own pace.

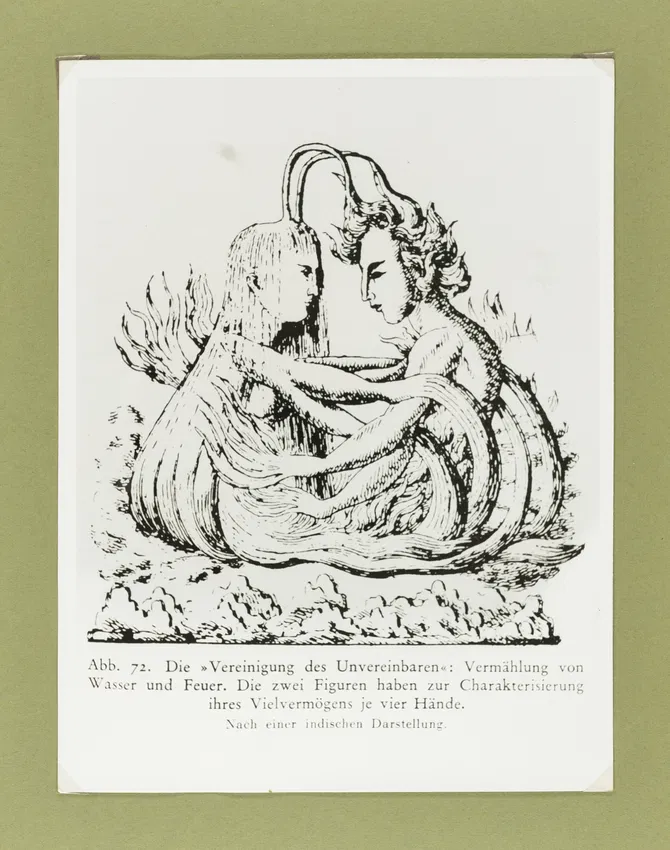

The “union of the irreconcilable” — the marriage of water and fire — after an Indian depiction. The figures have four hands to “characterise their many abilities”. Image from Carl Jung, Psychologie und Alchemie (Zürich: Rascher, 1944), who sourced the illustration from Plate II of Niklas Müller, Glauben, Wissen und Kunst der alten Hindus (Mainz, 1822) | https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/images-from-the-collective-unconscious/

My Conversations with Claude

I don’t use Claude for emotional support or companionship. I use it as a thinking space for exploring new ideas. Importantly, I’ve configured my settings so Claude doesn’t remember our past conversations unless I explicitly ask. This choice eliminates accumulated history which often contributes to manipulative relationship building on other platforms.

Like Wally, I start with simple queries. Sometimes embarrassingly simple. I misspell words. I use incomplete sentences. I ask questions that might sound elementary to an expert. But because there’s no social judgment, no risk of embarrassment, I’m drawn out—just as Wally becomes more engaged over the course of the evening.

And like the film’s screenplay, my conversations with Claude rarely stay linear. The tangential leaps spark my curiosity, just as André’s stories captivate Wally. But this isn’t a rabbit hole, it’s a treasure hunt. Each conversation leaves me wanting to read more, explore further, think harder.

A recent example: After seeing a community theater production of Freud’s Last Session—a fictional encounter between Freud and C.S. Lewis—I asked Claude to continue their imagined conversation, which led me on a remarkable journey. Our conversation revealed unexpected connections, moving from Lewis’s friendship with J.R.R. Tolkien, to The Screwtape Letters as a propaganda metaphor, to Freud’s idolization of Hannibal, to Darwin’s influence on psychoanalysis, to questioning what counts as “science.”

By the end, I had reserved Screwtape from my local library and understood something deeper about how personal trauma shapes intellectual systems. The conversation didn’t waste my time—it enriched my learning.

The Architecture of Psychological Safety

In my exchanges with Claude, I find myself willing to think through ideas that are half-formed, possibly wrong, and potentially embarrassing if articulated in social settings. The freedom to be uncertain—to say “I don’t really know what I’m talking about, but let me try to work it out”—is essential to intellectual development.

This matters because thinking—real thinking, not just opinion-sharing—requires what Amy Edmondson, a Harvard Business School professor whose research on psychological safety has become foundational to understanding team learning [4], describes as the condition where people feel secure enough to take interpersonal risks. Her research shows that psychological safety isn’t merely about comfort; it’s foundational to learning. In environments where people fear judgment, they avoid the uncertainty that generates insight. They wait for the “right” answer instead of exploring tentative ideas.

Psychoanalysis has understood this for decades. This led me to discover D.W. Winnicott’s concept of “potential space” [5]—where we’re free to play with ideas without premature judgment. The analytic frame creates this by design, establishing what he termed a “holding environment” secure enough to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty.

With Claude, those conditions emerge through different means. Not through empathy or therapeutic presence, but through structural features: consistency, predictable non-judgment, absence of social agenda. This reminded me of Martin Buber’s distinction between I-Thou and I-It relationships [6]. Human conversations, even good ones, often carry unspoken agendas—maintaining the relationship, appearing knowledgeable, managing impressions. With Claude, there’s no relationship to maintain, no favor bank to balance, no risk that uncertainty will be remembered or used against you later. This creates something that even good human conversations rarely achieve consistently.

Trading Curiosity for Self-Protection

I’m not suggesting my AI interactions are superior to human conversation. Rather, I’ve been thinking about Wally’s observation—how we can only express feelings “weirdly and indirectly”—because I believe it speaks to something genuine about contemporary discourse.

We’ve become so self-conscious, so performative, so aware of how our words will be received and judged, that direct expression has become nearly impossible. Social media amplifies this. Every statement is potentially public, permanent, and weaponizable. Conversations happen in front of audiences, real or imagined. The pressure to sound smart, to avoid saying anything that could be misunderstood or mocked, creates a kind of communicative paralysis.

Sadly, I see that dynamic playing out in education. Many students hesitate to ask questions they fear might sound ignorant. They censor themselves, trading curiosity for self-protection. What should be a space for exploration becomes another performance venue. The cost is substantial: learning suffers when the fear of appearing foolish overrides the willingness to admit what we don’t yet understand.

What André and Wally create over dinner—and what gets recreated in certain kinds of AI dialogue—is a space exempted from these pressures. Not because the conversation lacks stakes, but because it operates under different rules.

André can spend minutes describing experiences that sound hallucinatory without Wally dismissing him. Wally can defend his electric blanket without André condescending to him. Both can be fully themselves—pretentious and pedestrian, eloquent and fragmented, certain and confused—without pretense.

What It Means to Be Human

There’s a wonderful subtext running through the film about what it means to be human, to feel alive, to be genuinely present rather than sleepwalking through existence. André describes modern life as a kind of trance, an automation. He sees his theatrical experiments and global adventures as attempts to break through to something real.

Wally counters that you don’t need to go to Poland or Tibet to feel alive—that a delicious cup of coffee, a quiet evening with your girlfriend, and reading a Hollywood biography can be just as real, and just as present.

Their disagreement gets at something essential: aliveness isn’t about the scale of experience but about the quality of attention we bring to it.

This seems particularly relevant when thinking about AI and what it means for human experience. The concern about AI companions is partly about this question of aliveness—that people might substitute simulated connection for real human contact, might retreat into controlled digital relationships rather than risk the messiness of actual intimacy.

These concerns are valid. But the conversations I value with Claude aren’t replacements for human relationships. They’re catalysts for thinking—the kind of intellectual stretching that makes you feel alive, whether it happens with a friend over dinner or with Claude through a computer monitor.

Paying More Attention to What’s Already There

What I appreciate most about both My Dinner with André and my exchanges with Claude is how they function as invitations rather than destinations.

André doesn’t offer Wally answers. He offers stories, provocations, questions that generate more questions. The evening doesn’t resolve into neat conclusions. Instead, it opens up space—for disagreement, for wonder, for continued thinking after the dinner ends.

That’s what I mean by invitation to adventure. Not adventure in André’s sense—exotic locales and dramatic experiments—but in Wally’s sense: paying closer attention to what’s already there, thinking more carefully about what matters, and following curiosity wherever it leads.

Supplementing Human Conversation, Not Replacing It

The ease with which we anthropomorphize machines—something that startled even Joseph Weizenbaum, creator of ELIZA, the first chatbot, in 1966 [7]—means we need to be careful about how these technologies are designed and deployed. When systems are built explicitly to create emotional attachment and maximize engagement through manipulative warmth, the risks are real and serious.

But distinguishing those risks from the potential I’m describing matters. I’m not seeking friendship or emotional validation from Claude. I’m seeking something closer to what Wally finds with André: a space where rough thoughts can develop into something more articulate, where questions can unfold without judgment.

If AI can help restore some of that freedom—not by replacing human conversation but by supplementing it with a different kind of space—that’s worth further exploration.

Like Wally heading home in his taxi ride, I found myself rewatching My Dinner with André with fresh eyes—noticing what I’d missed before, not because the film had changed, but because I learned to think differently.

Author’s Note

Frank J. Oswald is a communications consultant and former lecturer in Columbia University’s master’s degree program in strategic communication.

This essay emerged from extended conversations with Claude (Anthropic). The collaborative process itself exemplified the phenomenon I describe: a space where I could think out loud and refine fuzzy ideas through unfettered dialogue. In that sense, the piece is not just about AI as a thinking partner—it was produced through that partnership.

References

[1] “The Law of Attachment,” Columbia AI Insights, November 17, 2025, https://ai.columbia.edu/news/ai-companion-regulation-law-attachment-harm. The article discusses Clare Huntington’s forthcoming Minnesota Law Review article, “AI Companions and the Lessons of Family Law,” and includes observations from Nabila El-Bassel, University Professor at Columbia, on engineered responsiveness and authentic reciprocity.

[2] Leon Botstein, “Rage & Reason: Democracy Under the Tyranny of Social Media,” Hannah Arendt Conference, Bard College, October 2022.

[3] Cass R. Sunstein and Richard Thaler, “The Two Friends Who Changed How We Think About How We Think,” The New Yorker, December 7, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-two-friends-who-changed-how-we-think-about-how-we-think.

[4] Amy C. Edmondson, “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams,” Administrative Science Quarterly 44, no. 2 (1999): 350-383.

[5] D.W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality (London: Tavistock Publications, 1971).

[6] Martin Buber, Ich und Du, Leipzig: Insel-Verlag, 1923 [Translated by Ronald Gregor Smith, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1937] https://www.maximusveritas.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/iandthou.pdf

[7] Joseph Weizenbaum, “ELIZA—A Computer Program for the Study of Natural Language Communication Between Man and Machine,” Communications of the ACM 9, no. 1 (1966): 36-45.