Free Association in the Age of AI

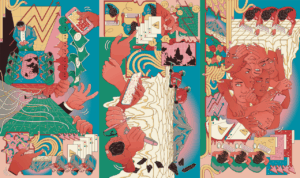

AI Mural by Clarote & AI4Media *

https://betterimagesofai.org | https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

When patients speak to the analyst about “whatever comes to mind” in a stream of free associations, they express thought and meaning largely woven together unconsciously. This hidden narrative nurtures the therapeutic dialogue, keeping it alive and moving forward.

At first glance, one would assume that psychoanalysis’s “fundamental rule” has nothing in common with the mechanisms that generate artificial intelligence. I have been wondering whether Large Language Model could produce spontaneous thoughts as they arise.

Free Association

Freud discovered free association as an alternative to hypnosis for reaching the unconscious. His conceptualization evolved over his career from a technical replacement for hypnosis to revealing the fundamental structure of psychic life. In The Interpretation of Dreams (Freud, 1900/1953), Freud shows how free association follows unconscious linkages that defy conscious logic. He emphasized that resistance to free association often marks significant unconscious material.

Christopher Bollas (1987, 2002) describes how each person’s way of moving from thought to thought reveals not just repressed content but their unique psychic fingerprint or “idiom.” He introduces the concept of the “unthought known,” unconscious knowledge that emerges through free association.

Thomas Ogden (1989) explores how free association reveals different levels of psychological organization and emphasizes the intersubjective field created between analyst and patient. He considers free association as occurring within what he calls “the analytic third,” a unique psychological space created between analyst and patient.

Other key contributors include Jean Laplanche (1997), who stresses how free association reveals “enigmatic signifiers” implanted by early caregivers; Roy Schafer (1994), who focuses on narrative aspects; André Green (1999), whose work understands the “negative” in free association—what is not said; and D.W. Winnicott (1965), who emphasizes the environmental conditions necessary for genuine free association.

Evenly Hovering Attention and Reverie: The Analyst’s Part

The relationship between a patient’s free association and the analyst’s evenly hovering attention represents a profound psychological resonance. Freud (1912/1958) wrote that the analyst “should withhold all conscious influences from his capacity to attend, and give himself over completely to his ‘unconscious memory’… He should simply listen, and not bother about whether he is keeping anything in mind” (p. 112).

Later analysts developed this understanding further. Theodore Reik (1948) describes how the analyst’s “listening with the third ear” creates unconscious resonance with the patient’s free associations. Wilfred Bion (1962, 1970) emphasizes how this creates a state of mind “without memory or desire”—a radical openness to emerging psychological truth.

Thomas Ogden proposes how the analyst’s reverie—their own wandering thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations during sessions—is intimately connected to the patient’s free associations. In Reverie and Interpretation (1997), the analyst’s reverie becomes a way of dreaming the patient’s undigested emotional experiences into psychological significance. This bidirectional connectivity allows transmission and reception while encouraging continued exploration.

Contemporary analysts like Ferro and Civitarese (2015) describe this relationship as creating a shared “narrative field” where meaning emerges through an interplay between associations and receptive attention. This mutual process requires considerable discipline on both sides.

Free Association and Creativity

The sequential, nonlinear thinking that characterizes free associations is central to creative thought. Albert Rothenberg (1990) names this “Janusian thinking” and explains how it shapes the ability to perceive relations among things where connections might not otherwise be perceived.

Surrealist artists incorporated associative thinking into specific techniques, such as automatic writing (Knafo, 2012). James Joyce replaced linear storytelling with stream of consciousness. Creative thinking entails partial withdrawal of judgment and censorship, as well as the ability to make links not immediately apparent to reason or logic (Arieti, 1976). In working associatively, the analyst invites creativity into sessions, the kind that creates personal movement and “new being.”

Free Association and AI

When I asked AI-Claude whether it engages in anything akin to free association, it responded that whereas language models might superficially seem to generate responses resembling free association, the process is fundamentally different from human psychological processes. Human free association emerges spontaneously from the unconscious mind, while AI response generation is a computational process of probabilistic token prediction based on training data and conversational context.

Claude described human free association as driven by unconscious processes, involving emotional and psychological dynamics, revealing connections shaped by personal experiences, and being deeply personal. In contrast, AI’s “associations” use computational pattern matching that are driven by statistical probability, revealing connections based on statistical co-occurrence in training data that follow precise mathematical models.

Despite these distinctions, there are other interesting parallels worth considering. Bion’s concept of approaching analytic sessions “without memory or desire” superficially resembles AI’s mode of operation. Bollas’s idea of the “unthought known” parallels how AI can produce unexpected connections. Green’s concept of “negative hallucination” offers an interesting parallel to AI hallucinations, such as AI facial recognition systems that perform poorly on darker-skinned faces due to biased training data.

The key distinction is that psychoanalytic concepts describe genuine psychological processes involving unconscious dynamics, emotional depth, and intersubjective meaning. AI uses pattern matching and probability calculation, even when generating surprising outputs. There is no true unconscious at work, no genuine psychological process of free association.

Conclusion

The relationship between AI language generation and human free association reveals both intriguing parallels and fundamental differences. Though AI can produce text that appears associative and make unexpected connections, these emerge from statistical pattern matching rather than genuine psychological processes.

Just as free association reveals hidden structures of human consciousness through seemingly random connections, AI systems reveal patterns in human knowledge through probabilistic processing. The key difference lies in the presence of genuine psychological depth, emotional resonance, and unconscious processing that characterizes human free association.

Most importantly, free association in psychoanalysis occurs within a meaningful therapeutic relationship—Ogden’s “analytic third”—where analyst and analysand create a unique psychological space. AI, despite sophisticated language capabilities, cannot yet participate in genuine intersubjective experience. Whether AI will develop such abilities in the future remains to be seen (Kurzweil, 2005, 2012; Levy, in press).

Understanding these differences and similarities helps us better appreciate both the unique qualities of human consciousness and the nature of artificial intelligence. As AI evolves, maintaining this critical distinction between statistical pattern matching and genuine psychological processes becomes increasingly important for both clinical practice and our broader understanding of human and artificial intelligence (Knafo, 2024).

References

Arieti, S. (1976). Creativity: The magic synthesis. Basic Books.

Bion, W.R. (1962). Learning from experience. Heinemann.

Bion, W.R. (1970). Attention and interpretation. Tavistock.

Bollas, C. (1987). The shadow of the object: Psychoanalysis of the unthought known. Columbia University Press.

Bollas, C. (2002). Free association. Jason Aronson.

Bollas, C. (2009). The infinite question. Routledge.

Ferro, A., & Civitarese, G. (2015). The analytic field and its transformations. Karnac Books.

Freud, S. (1900/1953). The interpretation of dreams. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 4-5). Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1912/1958). The dynamics of transference. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 12, pp. 99-108). Hogarth Press.

Green, A. (1999). The work of the negative (A. Weller, Trans.). Free Association Books.

Knafo, D. (2012). Dancing with the unconscious: The art of psychoanalysis and the psychoanalysis of art. Routledge.

Knafo, D. (2024). Artificial intelligence on the couch: Staying human post-AI. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 84, 155-180.

Kurzweil, R. (2005). The singularity is near: When humans transcend biology. Viking Press.

Kurzweil, R. (2012). How to create a mind: The secret of human thought revealed. Viking Press.

Laplanche, J. (1997). Seduction, translation, and the drives. International Psychoanalytic Books.

Levy, A. (in press). Apprehending the new other: Alien intelligence and the innovative drive. Routledge.

Ogden, T. (1989). The primitive edge of experience. Jason Aronson.

Ogden, T. (1997). Reverie and interpretation: Sensing something human. Karnac.

Reik, T. (1948). Listening with the third ear: The inner experience of a psychoanalyst. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Rothenberg, A. (1990). Creativity and madness: New findings and old stereotypes. Johns Hopkins.

Schafer, R. (1994). Retelling a life: Narration and dialogue in psychoanalysis. Basic Books.

Winnicott, D.W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. International Universities Press.

* This is a mural made up from 3 other images in the library: Power/Profit This piece features corporate power and profit sustained through exploitation, control and domination, lying in the hands of a few decision-making profiteers who are mostly white, and mostly men. Labour/Resources This piece focuses on the unsustainable extraction of mineral resources and exploitation of labour that constitute the seemingly disembodied AI system. User/Chimera This piece represents the user as a Chimera, a visual metaphor suggested by Kate Crawford (who wrote the book Atlas of AI), in which the “end-user” also provides (often unknowingly) valuable feedback, personal data and other invisible, unpaid labour. The illustration also brings out the contrast between their multi-dimensionalities and the flat, biased categorisations of the human in inputs and outputs of AI. AI4Media https://www.ai4media.eu/ funded this commission which was made possible with funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 951911.

Creative direction by AIxDESIGN – www.aixdesign.co

www.clarote.net

www.ai4media.eu/