Extended Minds, Ethical Agents, and Techno-Subjectivity in the Worlds of AI

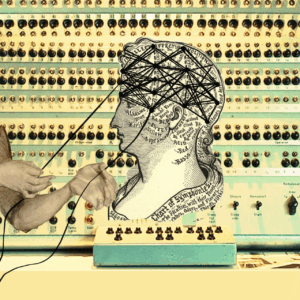

Turning Threads of Cognition by Hanna Barakat & Cambridge Diversity Fund * | https://betterimagesofai.org | https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Philosophers, theologians, and ethicists since Plato have worried about the meaning, role, and impact of technologies on all aspects of human existence. Plato thought that writing compromised memory. The invention of the printing press and the increase in literacy that came with it was thought to threaten established authorities and spread erroneous ideas. More recently, philosophers are concerned that the unprecedented degree of acceleration of technologies threatens to overtake our capacity to think through their long-term ethical implications not only for individuals, but for humanity itself. German theologian Jürgen Moltmann (2007) writes, “If science and ethics are separated, ethics always appears too late on the scene. It is only after science has taught us the methods of power that ethics is supposed to teach us power’s responsibility” (p. 140). Well before the emergence of AI, philosopher Hans Jonas (1974) warned that “Modern technology has introduced actions of such novel scale, objects, and consequences that the framework of former ethics can no longer contain them” (p. 8). Ethical theorizing and practice, he continued, are confronted with a “new dimension of responsibility never dreamt of before” (p. 9). Read in the current context not only of AI, but also the very real possibility that “we could have conscious AI before too long” (Chalmers, 2023, p. 3343), concerns about our ability to mount an ethical response commensurate with the current levels of AI technologies urgently demand our critical attention. The recently elected Pope Leo XIV identified AI as a threat to human dignity, compassion, and justice.

The anxieties articulated by Moltmann and Jonas around the challenges posed by advanced technologies to human welfare and flourishing are especially relevant in the world of AI and must be thought through more deeply. How can ethics begin to define and address this “new dimension of responsibility” as now augmented by AI? How can ethics be expanded to think through the nature of the relationships between human beings and the technologies they create? Even this formulation is somewhat misleading. Rather than thinking about our relationship with technologies, we need to radically reconsider our foundational notions of identity, subjectivity, agency, representation, symbolization, and consciousness—in short, all aspects of human mental and emotional life.

The philosophical approaches of both Moltmann and Jonas rest upon underlying assumptions that must be expanded to include the implications of the interactive interface between AI and human minds. The way they express the challenge to ethics posed by technologies is not wrong; it does not go far enough. Their main assumption appears to be that since technology and human beings interact in a subject-object relationship, human beings need to close the gap between technological achievements and ethics. They are calling for ethical technologies that serve human needs. However, the problem is that this way of conceptualizing the human-technology relationship assumes that each element has its own delimited reality. Writing in the long shadow of WWII, the Holocaust, the use and proliferation of nuclear weapons, and the growing threats to the entire human and nonhuman biosphere within which all life originates and is sustained, Moltmann and Jonas point to the vulnerability and precariousness of human existence. They are well aware that the “novel scale” of modern technologies is foreclosing on possibilities for meaningful ethical interventions commensurate with our current reality.

What kinds of critical questions are needed to address the ethical and philosophical challenges posed by AI? To address these questions, we must consider how the things we create also create us. In other words, we must consider how human embodiment and material artifacts comprise a comprehensive “potent whole” or “cognitive entwinement” (Clark, 2023, p. 151) with the world in which we live. This is what Moltmann and Jonas do not address.

The cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1973) intimated the need for a reconceptualization of human and culture entwinement when he wrote “there is no such thing as a human nature independent of culture. Men without culture … would be unworkable monstrosities” (p. 49). Here I read Geertz gesturing toward “Material Engagement Theory” (Malafouris, 2013), which argues that tools and artifacts not only shape human minds, they extend them “into the extra-organismic environment and material culture” (227). For Lambros Malafouris, this means that “mind” and everything in the “material world” are mutually constitutive all the way down (227). From this perspective material culture is not the strictly objective product of a pre-existing mental representation produced and contained within individual human minds. Malafouris insists that minds are distributed or “spread” throughout their environments. Concrete artifacts are understood as “immediate and direct” “cognitive extensions” of an enactive, embodied and embedded mind. This is a version of the extended mind hypothesis advanced by Andy Clark and David Chalmers (1998) that challenges us to rethink the human mind not only as a product of “biological evolution” but also as, according to Malafouris, “an artefact of our own making”, or “artefacts of their own artefacts” (231). Malafouris goes even further to postulate an ontology of non-human artifacts that I argue logically includes machine-generated intelligence, or AI.

Philosophically, the idea that human subjectivity and objectivity are mutually constituted is not new, as can be seen in the work of Theodor Adorno. For Adorno, the idea of a subject that exists independently of an object is an Enlightenment myth that underwrites dangerous impulses toward mastery and subjugation of all human and non-human life (2002). Malafouris’s idea that interior mental life is “inseparably linked with the ‘external’ domain” (236) is philosophically resonant not only with Adorno’s understanding of the mutually constitutive relationship of subject and object, but also with Clark and Chalmers’s (1998) view that external materiality plays “an active role … in driving cognitive processes” (p. 7).

A psychoanalytic approach to these ideas would add that not only cognitive processes shape and are shaped by the products of material culture, but emotional and unconscious processes are as well. As Luca Possati (2023) rightly observes, human unconscious dynamics inevitably influence the development of technology (p. 52). If agency, intentionality and consciousness are considered as distributed, it follows that the unconscious, with all its conflicts, fantasies and contradictions, is also distributed. No aspect of the human mind is limited to the operations of the physical brain. Although Malafouris does not mention the unconscious, he does argue that the distributed aspects of mind are not limited to the human realm. Rather, he sees them as “emergent properties” of enactive “material engagement” (Malafouris, 149).

We can better understand what Malafouris means with reference to a cinematic vignette from the opening scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey that depict the daily life of a small primate community beleaguered and besieged by aggressive rivals, predators, and the constant scarcity of food. Kubrick shows these primate human ancestors huddling together at night in caves with fear clearly expressed on their faces as they listen to the threatening sounds made by unseen beasts lurking nearby. The scene that is most relevant to the discussion here shows an adult male idly playing with the bones of a skeleton of indeterminate origin. He has no apparent purpose in mind. Then almost by accident he picks up a large thigh bone and starts to hit it aimlessly against the smaller bones. As they crack and splinter, a cognitive change takes place that can be seen in the expression on his face. Through a quick series of images Kubrick presents as located in the mind of the primate, we see how the realization slowly dawns upon him that the bone can be used for multiple purposes, such as hunting animals for food and fighting off rivals. With the transformation of the bone into a tool, the group gains both physical strength from eating small animals and the psychological confidence to confront their primate rivals, who they vanquish and kill.

This sequence of opening scenes in the film shows how the primates’ bodies, cognition, and emotional affects have been changed by the tools they created. Winnicott’s idea of the transitional object is relevant here, as the bone that becomes a tool is both discovered in the external world and created in the mind, opening pathways to future space exploration. A psychoanalytic interpretation of this cinematic vignette would point out that the entire interactive process was driven by the primates’ feelings. Their felt need for food, safety, and security in the service of physical survival in an enactive engagement with their material environment changed and expanded their cognitive processes, sparking more sophisticated capacities for mental representation and the emergence of subjective and collective agency.

What does all this mean for the efforts of psychoanalysis to meet the challenges facing it theoretically and clinically within the context of the rapid proliferation of AI in all areas of social and individual life? The popularity of AI companionship is growing, from reliance on “expert” advice from chatbots on navigating the return of commercial purchases, to assistance with research in any field, writing academic papers, grief counseling, psychotherapy, romantic relationships, or ordinary friendship. All of these services generate huge profits for the companies who make them. In a recent Wall Street Journal article (May 7, 2025) Mark Zuckerberg’s “vision for a new digital future” was described as affording people opportunities for increased numbers of friends and access to AI therapy bots. “I think people are going to want a system that knows them well and that kind of understand them in the way that their feed algorithms do,” Zuckerberg is quoted as saying. He predicts that for those people who don’t have a human therapist, “everyone will have an AI” therapist. People need chatbots who behave like good friends, with a “deep understanding of what’s going on in this person’s life.”

The news media is full of stories about people who have therapy bots, grief bots, and machine-generated lovers. Some report that they feel more validated and comforted by their therapy bot than their human therapist. Others say that their bot lovers are more comforting, and sometimes sexier, than their human partners. The seductive power of AI relationships with bots designed for any particular role has little to do with the user’s intellect and knowledge. Rather, it is accounted for by the needs and the feelings that must be satisfied. No matter how intellectually powerful an argument may be that exposes the negative consequences of using AI to counter feelings of loneliness, isolation or grief, it is ineffective unless the feelings produced by the interactions with bot companions are addressed. As Todd Essig offered in a recent APsA seminar, “AI doesn’t care if you get to the grocery store or drive off a cliff.”

Insights like this, no matter how reasonable they are, remain ineffective in convincing people of the emotional harm AI generated relationships can cause unless the feelings about these relationships are addressed in other ways. Because psychoanalysis understands that psychological change cannot occur through intellectual insight alone, it has the capacity to intervene effectively in public discussions concerning the worrisome consequences for mental health as AI undermines psychological growth.

Psychoanalytic concepts of the unconscious, transference, projection, fantasy, and dissociation (to name a few) can provide a depth and complexity of understanding that is needed to highlight the potentially destructive impact of AI on mental life. It can also provide insights into beneficial and healthy ways that AI might be used to supplement and support avenues for improving and expanding mental-health treatment and wider access to quality education, for example. Psychoanalysis can call attention to the damaging effects of AI whose main purpose is directed to the accumulation of power and wealth for a few, or to its potential for the improvement of the quality of life for the majority of human beings on this planet. This brings the discussion back to the ideas of extended minds, material engagement theory, and the mutually constitutive nature of human beings and the technologies they produce, and that produce them. We are hybrid creatures who exist in a “complex web of biological and non-biological structures” (Clark, 2023, p. 153). We have only to think about the importance of our iPhones, and the panic we experience when they are lost. They are not just extensions of our minds or memory. They constitute a part of our cognitive structure, thus revealing the “surprising fuzziness of the self/world boundary” (p. 154). Our minds, our sense of self are so “intimately bound up with the worlds we live in that damage to our environments can sometimes amount to damage to our minds and selves” (p. 154).

Psychoanalysis must take this into account in its theorizing and clinical practice, recognizing that both analyst and patient inhabit the same world and are impacted by technologies in similar ways. At the same time, psychoanalytic theories provide not only the emotional and mental space for critical thinking about the threats to our shared humanity posed by AI technologies, they can also contribute to formulating effective ethical interventions in directing them in the promotion and service of human wellbeing.

References

Chalmers, David J. (2023). “Q & A: David J. Chalmers”. Neuron 111, 3341–3343.

Clark, Andy & Chalmers, David. 1998. “The Extended Mind”. Analysis, 58/1: 7–19.

Clark, Andy. (2023). The Experience Machine: How our Minds Predict and Shape Reality. New York: Vintage Books.

Geertz, C. (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essys. Basic Books.

Horkheimer, M. & Adorno, T. W. (2002). Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. E. Jephcott (trans). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Jonas, H. (1974). Philosophical Essays: From Ancient Creed to Technological Man. University of Chicago Press.

Malafouris, L. (2013). How Things Shape the Mind: A Theory of Material Engagement. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Moltmann, J. (2007). The Future of Creation: Collected Essays. Fortress.

Possati, L. M. (2023). Unconscious Networks: Philosophy, Psychoanalysis, and Artificial Intelligence. New York: Routledge.

* ‘Turning Threads of Cognition’ is a digital collage highlighting the historical overlay of computing, psychology, and biology that underpin artificial intelligence. The vintage illustration of a head (an ode to Rosalind Franklin, a British chemist who discovered the double helix of DNA) is mapped with labeled sections akin to a phrenology chart. The diagram of the neutral network launches the image into the modern day as AI seeks to classify and codify sentiments and personalities based on network science. The phrenology chart highlights the subjectivity embedded in AI’s attempts to classify and predict behaviors based on assumed traits. The background of the Turing Machine and the two anonymous hands pulling on strings of the “neural network,” are an ode to the women of Newnham College at Cambridge University who made the code-breaking decryption during World War II possible. Taken together, the collage symbolizes the layers of intertwined disciplines, hidden labor, embedded subjectivity, and material underpinnings of today’s AI technologies.

http://www.hbarakat.com

http://www.race-equality.admin.cam.ac.uk/university-diversity-fund