Are Translators Necessary? A Case Against AI

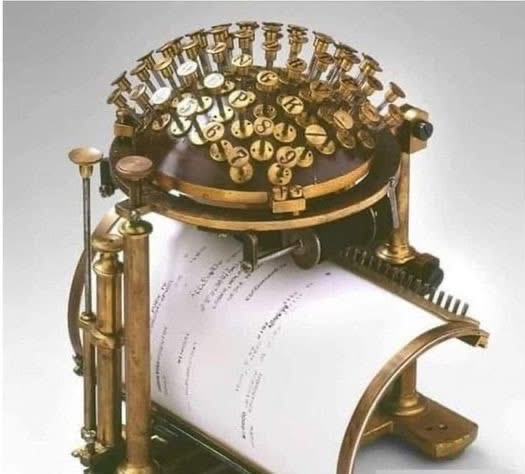

Malling-Hansen writing ball, 1865

On November 11, 2024, the Guardian ran a piece online. The title was “‘It gets more and more confused’: can AI replace translators?,” and it was prompted by Dutch publisher Veen Bosch & Keuning (VBK)‘s announcement that it was opening its door to AI translation of fiction. According to the article, VBK specified that “this project contains less than 10 titles–all commercial fiction. No literary titles will nor shall be used. This is on an experimental basis [emphasis mine].” Nonetheless, authors and translators criticized this decision, and VBK reiterated previous statements from a November 4 Guardian article that AI would be used only with the author’s permission, and that “We are not creating books with AI, it all starts and ends with human action.” These qualifications are not reassuring, however.

“On an experimental basis” deserves special attention. A translator like me might run a challenging text I had translated through GoogleTranslate out of curiosity, but a publisher trying AI just to see what happens would probably see no reason to announce it. Especially these days, when big tech is pouring vast amounts of money into the race to dominate AI–a technology intended to produce complex products like translation quickly and cheaply and so maximize profit for corporate stockholders.

The November 4 Guardian article points out that VBK had been bought six months earlier by Simon & Schuster (S&S). Not mentioned, however, was that that mega-publisher had itself been bought a year earlier by the private equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts. In other words, S&S’s primary responsibility is no longer just creating a quality booklist but generating profits for investors. A recent New York Times article explained that Meta (owner of Facebook and Instagram) had had its eye on S&S too: not to publish its vast reserve of books, but to absorb their content and so enrich Meta’s developing AI technology enough to challenge ChatGPT. Information like this makes VBK’s comment about a ten-book experiment sound more than a little disingenuous. And very worrisome.

For a long time, we translators believed that stylistic and emotional complexity would keep AI out of literary translation. The developers of so-called translation memory tools assured translators 25 years ago that their products were designed to assist in the translation of commercial and technical texts by supplying suggestions gleaned from corpora of previous translations. Nothing to worry about, they told us: “Jump in, the water’s warm.” And for a while those tools were a convenience for some of us. But translation agencies soon began forcing translators to use them, and then increasingly to control the translation process.

They decreased per-word rates on the grounds that translation memory tools were doing a lot of the work, but they were slower to recognize that this help came at the cost of quality. Machine-generated output may be comprehensible, but it is not necessarily optimal. And this became a paradoxical problem for translators and agencies both. Less fairly compensated for their time and effort, translators were under pressure to let “good-enough” formulations pass; the agencies applying the pressure worried about the result. Their solution, however, was not more autonomy for human translators, but a frantic search to improve the competence of AI. The water became considerably chillier.

The Times piece makes clear that the powerful movers of AI development are playing a long game, striving to reduce the nuanced qualities of text to calculable quantities of data in as many areas as possible, and so to reduce dependence on skilled, and expensive, human labor. The more successful this effort is, the more authors and translators—that is, those who interpret personal experience, as opposed to generic information—may become victims of digital Fordism. Like the expert mechanics who were forced to abandon their craft in favor of automobile assembly lines at the turn of the last century, skilled translators are increasingly seen as dispensable. I began chronicling this process as an exercise in 2015; here’s one example:

As the profit potential of AI wrought drastic changes in the corporate translation industry, venture capitalists and private equity firms invested heavily, expecting equally hefty returns. The result was the rise of a few mega-agencies that began buying up specialized translation companies for their market share. In 2015, England-based RWS Group bought Corporate Translations, Inc., a highly respected small Connecticut medical translation agency, for $70 million. Two years later it bought Czech-based Moravia for $320 million. By June 2017, RWS had announced that it was replacing its more than 100 internal translators with post-editors of machine translations, because “[translators] are our most expensive resources.”

Certainly, standardization and efficiency are sometimes beneficial and/or necessary. But they do not automatically compensate for professional skill and experience, to say nothing of the pride and independence that these confer on individuals. The newfound wealth of the mega-agencies came at a terrible cost to human translators. Money was one such cost, of course, but my point here is that the corporate migration of translation from people to machines has effects far beyond the obvious financial one–on translators, on the work itself, and on its consumers.

One effect is the increasing scarcity of engaging and desirable work for expert translators, as the new environment offers unsatisfactory substitutions. Slator.com, an on-line publication that calls itself “Language Industry Intelligence” and that has been a cheerleader for industry consolidation and AI, has improbably maintained that “linguists are actively upskilling” in response to the evolving corporate market. It offers an optimistic view of the resulting new job opportunities: “Tasks for which linguists are being hired other than machine translation post-editing (MTPE) include AI prompting, terminology management, data management, and categorizing, labeling, and annotating data to train large language models (LLMs).”

None of these cited “tasks,” however, including post-editing, are in fact translation. They are functions of a digital assembly line, and they “upskill” neither translators nor their output. In a statement released in 2024, the Société française des traducteurs made the point that “tools like ChatGPT, which was released in 2023, are statistical estimation software,” and goes on to point out a serious risk: “generative AI produces partially or wholly false information by presenting it as true, because it prefers to “hallucinate” when it lacks data, rather than remain mute. [emphasis in original]” Generative AI hallucinates because it cannot ask critical questions, and translators who are hired as post-editors may not have the time or inclination to ask them either. Quality is impossible in the absence of the kind of thinking that results in questioning. Again, rather than upskilling its users, these translation tools impoverish both their editors and their readers. Whatever Slator wants to tell us, translators have gained nothing either financially or professionally from this change.

The demotion of translators from autonomous linguists to obedient servants of technology is dire in another way, too. Serious pursuit of any demanding discipline transforms both its practitioners and their work. Dedicated translators who engage with, say, complex legal or scientific texts learn to understand, absorb, and reproduce styles of thought that inform their own thinking, and by extension the translations they produce. This is not only through the research that expert translation often requires, but even more because a translator’s relationship with the text and its message deepens as he or she continuously grapples with the challenge of conveying the conventions, modes, and expectations of one language into another.

This transformative potential of translation is especially potent in work with literary and personal (i.e., non-technical) texts. In the years I’ve spent translating scholarly works, diaries, and bodies of letters, I’ve often felt like a guest in the mind of the author, invited there to identify with and emulate his or her thought processes. With a living author, this can result in a back-and-forth, clarifying not only the translator’s understanding, but not infrequently that of the author as well. The translator’s commitment is to the text and to the author both, and one result of it is that translations sometimes diverge from the original work–often to its advantage. The alliance that forms between author and translator can be profound; in my case, one such relationship lasted more than 20 years. But responsible and responsive literary translation is a lot of work. Multiple drafts are not uncommon, and to prescribe a single edit (as VBK does) is ludicrous. How likely is it that a post-editor processing machine output at a lowered pay rate will develop such a commitment to the text, to the person who produced it, or to the opportunity for personal growth?

Identification and interrogation as essential aspects of translation are not limited to living authors. I translated more than 400 letters written in the 1880s between a young German governess working in Constantinople and her mother at home in Pforzheim. The problems of deciphering old script were trivial compared to the real responsibility of the task: to understand the experience of a 19-year-old woman from another era living in a place and a situation that were totally foreign to her and to me. That is why, among other things, I read one of the potboilers that she had turned to in times of discouragement (this one was Eugene Sue’s The Mysteries of Paris). That book helped me understand her struggle to maintain a sense of her own “nobility” even though she was working in an often challenging position.

Processes like these are how we intuit the thought-based and emotional worlds of others in our lives. They are acts of imagination, informed by ever-finer images of the other and elaborated over time with an engagement similar to the one that characterizes deep translation. Did my image of this young woman bear any resemblance to the actual person? There’s no way to know. Another translator might well have pulled different qualities out of the letters. Still, I have to think that either one of our translations would have been more vibrant, and truer to her experience, as a result of our efforts. The capacity for this kind of reflection is the basis for empathy, without which relationship, understanding, and other meaningful aspects of personhood are impossible. But AI programs cannot reflect on personal experience or development because they have undergone neither; they can rely only on algorithmic logic.

************

Well then: can AI help inexperienced translators get started, and prepare them for broader choices later on? At a 2011 conference of the New England Translators Association, I asked the speaker Alon Lavie, a proponent of machine translation who is now a researcher and advisor in AI that question. “Is there anything about machine translation that would enable translators to develop the higher skills needed to translate more demanding material?” His answer was telling: “I don’t think there’s anything; but I’m not sure there’s anything in translation memory tools either.”

This was an admission that reliance on machine translation (and by extension AI) bypasses the intense engagement by which translators develop ever-increasing levels of understanding and expertise. AI proponents argue that this deficit will be remedied by improvements in the technology and (as happened at RWS) by enlisting translators as post-editors of machine output. But there is a vast difference between grappling with the sweep and complexity of ideas present in whole text, and correcting superficial errors of grammar, voice, and vocabulary in text produced by a machine, with which one is familiar only in passing, and not personally committed to.

So far, corporations are dismissing this understanding of translation as fundamentally incompatible with their profit motive. Henry Ford increased pay to keep his assembly lines humming, but today’s digital Fordists are making no such move. Translators are simply being eliminated. And we have to ask what this trend portends for teachers? doctors? psychotherapists? lawyers? The push to sideline human beings goes well beyond translation, and the loss is much more than money. I recently received an email from a historian friend in Germany:

“I attended a lecture on “AI in university teaching” last week, and the lecturer (of informatics) had no idea about the work a human or social scientist does. He was totally ok with AI writing the “texts” from scratch, especially for students. His own ideas were more about the “scientific” level of sciences. I was quite shocked. That means that there is no need for historians any more…. It will be hard work to convince people in (financial) power about the relevance of humanities!”

It is easy to see how translated texts and those who translate them are diminished by the limitations of algorithmic technology. Certainly, it is not the duty of corporations to provide translators (or anyone else) with growth experiences. But we must all eventually face the question of whether we want to live in a society in which humans are increasingly pushed aside, de-skilled, demoralized, and disconnected. AI advocate Slator recently conducted a survey that purported to show that “Over 50% of Freelance Linguists Have Thought About Changing Career.”

That’s no surprise, given the losses of compensation, competence, and engaging work. But in counting our losses we must also remember our readers, the broad audience for whom both authors and translators work. What will the effect be on them of the “flattening out” that machine translation enforces, with its reliance on statistical estimates? Will readers too become less skilled and less discerning as a result? Will their interpersonal understanding be eroded? If AI is de-skilling for translators, what will it mean for the young people who turn to it increasingly to produce essays on topics of which they know nothing? In an AI society, how will they develop enough experience of thoughtful analysis to allow them to judge what AI coughs up? And the same questions arise in all the other professions where artificial “intelligence” is slowly taking the place of the real kind. Most frightening of all, we must consider what “artificial intelligence” is doing to the natural human intelligence on which we build relationships, science, art, and society, and to the search for understanding that is our only reliable defense against the dangers of life in the real world.

In short, what might be the cumulative effect of AI on society at large? Will it contribute positively to the evolution of language and communication in this ever-changing world? Or will it eventually limit what can be thought and written and said?

We don’t know the answers, but it looks as though we’re about to find out.

==================

Licensed by Kenneth Kronenberg under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License, 2025

Kenneth Kronenberg has 30 years of experience as a German-to-English translator specializing in intellectual and cultural history and 19th– and 20th-century diaries and letters. In his retirement he is translating Nazi eugenics and texts aimed at the Hitler Youth, to better understand the nature and political program of Trumpism. He is currently translating Heinrich Krieger’s 1936 Das Rassenrecht in den Vereinigten Staaten (Race Law in the United States).