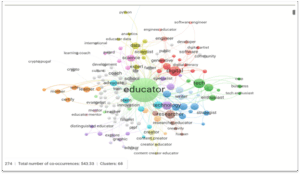

AI Educators: Enthusiasts, Entrepreneurs or Evangelists?

Educator [https://nocodefunctions.com/user_created_files/vosviewer/index.html?json=public/vosviewer_7529421792317800680.json]

The postmodern era has triggered the erosion of traditional authority figures in Western societies. This has reverberated through various professional positions, but none more than the teacher or educator. Hannah Arendt’s well-known essay, “Crisis in Education”, concerning the deterioration of the role of parents and educators as authority models in American society during the 1950s has gained significant traction since then. Today’s crisis in education is also noted by allied healthcare professionals, including social workers and psychologists, who regularly witness students’ lack of respect and violent behavior when called to duty in public schools.

The general acceptance of this decline in authority likely stems from a misunderstanding of the term, which is linked to fears arising from world-historical events where strict and totalitarian governments wielded excessive power, harming and victimizing thousands of civilians; this has led to today’s confusion regarding terms like authority, especially after postmodernists sought to challenge it in the educational context (Zamir, 2021). Despite skepticism towards professional authorities, the 21st Century is not liberated from authoritarian governments. Quite the contrary, such attitudes have expanded into other systems in today’s society with the support of technological advances. This trend is evident in industries like digital technology and artificial intelligence, which foster technocratic systems. Thus, to avoid such terminological confusion, I propose to use an alternate word – “ethos.” Ethos has its roots in Greek philosophy (i.e., Aristotle) and can be framed from psychoanalytical concepts of ego and id. In the Freudian system, the ego is the part of the mind that negotiates with the external physical world on various levels, creating meaning that can be expressed by the individual’s ethos, character, and integrity. The articulation between ego and ethos is thoroughly discussed in Williams’ article Ego and Ethos (2016) in the development of individuals’ identities, be it personal and/or professional.

Hence, professional ethos, as understood here, is not limited to one’s sole credential and account of expertise or specific subject knowledge. Rather, it encompasses an individual’s character, empathy, and ethics which are embodied in their professional attitudes, decision-making, speech, actions, and interactions.

The gradual erosion of professional ethos, which implies trust, respect, and agency for educators, has also been noted for healthcare professionals, such as doctors, psychologists, and therapists. The causes can be various, including, for example, professional abuse and errors. However, a more probable cause for such a consequence, as I speculate here, is the advancement of technology since the “digital renaissance” (Rushkoff, 2022) in the 1990s, which reduced the importance of professional ethos in society by bringing instability, uncertainty, and devaluation of professional identities and practices.

The shift from teacher-to-learner and therapist-to-patient-centered (or consumer-centered) approaches favored the mass production of goods, tools, and strategies to meet individuals’ learning and wellness needs and goals, such as cognitive enhancements and emotional and physical fitness. Since the last decades of the 20th Century, there has been an explosion of self-help references, mostly in the form of best-sellers marketed to teach people to deal with emotional crises and improve physical well-being. The digitalization of those resources has further facilitated their accessibility, making much of it freely available online through a variety of popular platforms. These include YouTube videos posted by professionals and amateurs across many academic fields; e-learning and e-therapy websites; and, more recently, applications that can be directly downloaded to people’s smartphones or mobile devices to enable users to, apparently, learn any academic subject, practice mindfulness, engage in CBT strategies, get fit, or even perform self-diagnosis. More so, generative AI technology can now enhance many of these applications with the widespread use of chatbots, the latest technological development in human-machine interface and interaction, dystopically commercialized to replace teachers, coaches, therapists, and doctors.

While those once well-established professional identities (e.g., teachers, therapists, doctors) may see their roles threatened with apocalyptic effects, paradoxically, new professional roles have emerged in the generative AI industry: prompt engineers, AI influencers, and AI educators. They use social media platforms to promote themselves and their products. Moreover, their roles make use of innovative rhetoric that supports their existence and functionality in the AI technology industry. AI educators, as an example, draw on a well-established understanding of “educator” as an umbrella term for a wide array of professionals such as teachers, doctors, nurses, psychologists, and therapists; they each care for the cognitive, emotional, and physical development and wellbeing of an individual. The notion of educator is also grounded in Western and non-Western traditions through various roles as teachers, mentors, priests, gurus, elders, and shamans, among others. In these traditions, the educator organically acquires a position of trust, respect, and admiration (ethos) in their community, as they can transmit knowledge and wisdom to the next generation.

Yet, adding the prefix ‘AI’ to the term ‘educator’ may disrupt our understanding of what an educator is, as it seeks to move away from traditional Western and non-Western cultural and cognitive schemata. As seen mostly on social media, in particular on the X platform, AI educators self-identify as tech enthusiasts and advocates who showcase and commercialize new AI products, such as generative AI tools for educational institutions, schools, teachers, and students. They are neither concerned about education, teaching, and learning matters, nor about the cognitive and emotional well-being of their users or consumers. Indeed, the term “educator” has been misappropriated from its original meaning, which encompasses ethos, authority, trust, and knowledge.

In today’s technocratic context, this misrepresentation serves as a rhetorical strategy to obscure the power of AI technology, which can lead to uncanny sensations (Das Umheiliche). By using a familiar figure instead, such as a teacher/educator, AI technology can be better orchestrated and accepted. This rhetorical move has led me to investigate those AI educators’ profiles on the X platform. My recent initial study shows that those individuals are invested in advertising and profiting from AI tools for educational purposes, mostly higher education, as an economic strategy to survive the current volatile and fragile market while they identify themselves as “entrepreneurs,” reaffirming neoliberal trends in today’s education.

Reinventing and leveraging professional identities is crucial in the current climate. Thus, most AI educator profiles indicate that the majority are male professionals with degrees in technology who exhibit a utopian mindset or optimistic attitude towards GenAI technology. Many endorse the mission of persuading institutions, instructors, and students to become AI ‘prosumers’ by engaging with digital teaching and learning tools to enhance their efficiency, productivity, and educational outcomes.

Their profiles push a consuming narrative, reducing the educator to a marketer, influencer, or salesperson who advertises and propagates an ‘educational tool’ that can free the teacher or student from labor, enabling more time for themselves while accomplishing their professional tasks with minimum effort. However, authentic teaching and learning require effort. Motivation, time, and labor are necessary ingredients to achieve true learning.

As AI educators present themselves as digital experts, strategists, and futurists with backgrounds and expertise in STEM fields, content creation, and data science research, they are, in fact, redefining the qualifications of the 21st-century educator: tech-savvy, a developer, a tech enthusiast, and an entrepreneur. In a way, the AI educator challenges the traditional association of public school teachers, which was predominantly a female role in the 19th and 20th centuries with humble salaries, motherhood and domestic values.

With this in mind, the AI educator creates a rhetoric to potentially replace the image of the traditional teacher with AI-embedded educational tools, GenAI platforms, chatbots, and cognitive robots, reconfiguring how we teach and learn. This approach is evident in their X-platform profiles. Moreover, AI educators hide ideologies that may envision the demise of the incarnate educator, teacher, or instructor while visibly publicizing embodied AI tools. However, the enthusiasm in those profiles seems artificial, with inflated egos and deflated ethos fueled by a fight for economic survival and driven by greedy algorithms to increase followership.

As AI educators’ presence is firmly fixed on the X platform, it’s hard to imagine them entering a real inner-city school classroom where chaos is the norm. Instead, we are stuck with their ego and ethos in a virtual reality, leaving us to question whether AI educators are fast-trackers of social disruption or enthusiastic evangelists of a new technological era in education.

References

Arendt, H. (1961). Crisis in Education. In: Between past and future. Penguin.

Freud, S. (2018). The Uncanny. Dialogues in Philosophy, Mental & Neuro Sciences, 11(2). https://www.crossingdialogues.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Ms-E18-02.pdf

Rushkoff, D. (2022). Survival of the richest: Escape fantasies of the tech billionaires. WW Norton & Company.

Valente, A.C. (2025) “The Educator in the GenAI Movement: Destabilizations, Otherness and Discourses” online presentation at the DN32 conference, Discourse Across Cultures, Transilvania University of Brașov, Romania, March 20 – 21, 2025. https://dn32-dac.unitbv.ro/images/DN32_Book_of_abstracts.pdf#page=19.75

Williams, David R. (2016). Ego and Ethos. In.: Ciprut, J.V. Ethics, Politics, and Democracy: From Primordial Principles to Prospective Practices. MIT Press.

Zamir, S. (2021). Teachers’ Authority in the Postmodern Era. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 10(3), 756-767.