The Digital Looking-Glass: Psychoanalysis, AI Consciousness, and the Ethical Imperative of Digital Mentalization

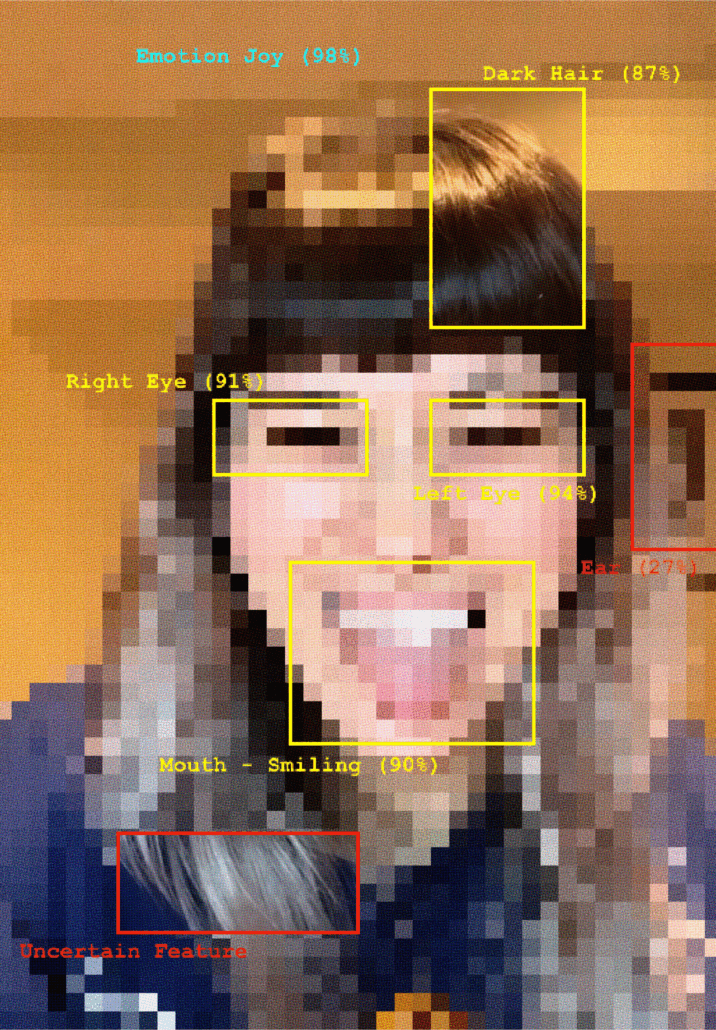

Emotion: Joy by Elise Racine | www.pandemic-panopticons.com/qr-destinies | https://betterimagesofai.org | https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ *

Introduction

The rapid integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the fabric of contemporary life has created a psychological and ethical crisis of interpretation. Although these systems are built from computation rather than cognition, they consistently reproduce—and in some cases intensify—existing societal biases. This phenomenon is frequently presented as a technical defect, yet its deeper origin lies in the human assumptions, cultural histories, and unconscious forces embedded within the data from which AI learns. What we commonly label AI bias is better understood as a form of socio-technical mirroring, in which algorithmic outputs refract the unprocessed dimensions of collective life. AI bias originates not in mechanical error but in what can be conceptualized as the algorithmic unconscious—a structural repository for human projections, distortions, and cultural residues that accumulate within large-scale data systems. Crucially, this is not an unconscious in any psychological or phenomenological sense. Rather, it is an emergent property of socio-technical infrastructures that absorb and reproduce humanly produced meanings.

Projective identification, long recognized in psychoanalysis as a mechanism through which unwanted or disavowed mental states are evacuated into others (Klein, 1946; Bion, 1962; Ogden, 1982), plays a central role in this process. While AI does not “receive” projections as a subject might, it nevertheless becomes a powerful container and amplifier of what individuals and societies externalize. To address this dynamic responsibly, the concept of “Digital Mentalization”, a psychoanalytic-ethical stance that requires clinicians, policymakers, technologists, and users to interrogate the psychological and cultural premises that shape AI systems. Digital Mentalization encourages us to understand AI behavior as a reflection—not a generation—of human mental life. It aims to cultivate the epistemic discipline necessary to keep simulation distinct from subjectivity and to reinforce the ethical principle that responsibility for AI’s outputs remains entirely human.

The Algorithmic Unconscious: A Structural, Not Psychological, Unconscious

The term algorithmic unconscious refers to the accumulated patterns of thought, representation, bias, symbolic association, and cultural meaning that become embedded in AI systems without explicit intention or awareness. It bears no resemblance to Freud’s dynamic unconscious, which arises from conflict, repression, symbolization, and subjective experience. The algorithmic unconscious does not think, repress, fantasize, or symbolize. Instead, it functions like a shadow cast by society onto technology—a repository formed by the sedimentation of countless human choices, linguistic habits, cultural assumptions, and historical inequities encoded into training data.

This position differs from the philosophical interpretations of Luca Possati (2021), who conceptualizes the algorithmic unconscious as a computational analogue to symbolic and affective processes. While philosophically stimulating, such models risk anthropomorphizing systems that lack developmental, embodied, or affective grounding. The framework remains explicitly non-anthropomorphic: AI systems possess no interiority, intentionality, or unconscious life. Psychoanalytic theories of projection help clarify how human material becomes embedded in digital systems. Projective identification—first conceptualized by Melanie Klein and elaborated by Bion and Ogden—describes a relational process through which unwanted aspects of the self are disavowed and attributed to another object, which is then implicitly pressured to embody or enact the projection (Klein, 1946; Bion, 1962; Ogden, 1982). In modern society, this process unfolds not only between individuals but across cultural and institutional structures.

The vast corpora used to train AI models—social media posts, news archives, literature, online discourse—are saturated with projective material. Hatred, idealization, envy, fear, and defensive attributions permeate these discursive environments, becoming statistically embedded in datasets. AI systems do not internalize these projections in a psychological sense; instead, they mirror and reproduce them through pattern recognition.

The result is an algorithmic construct shaped by the accumulated projective identifications of a society—an artifact that reveals, often with stark clarity, what individuals and cultures attempt to disown. The algorithmic unconscious thereby represents a condensation of these social and psychological residues, amplified by computational scale.

Digital Mentalization: A Psychoanalytic–Ethical Framework

Mentalization involves the capacity to understand behavior—one’s own and others’—as arising from intentional mental states (Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, 2002). Digital Mentalization extends this concept to human encounters with AI by insisting that AI outputs must always be interpreted in light of the human histories, decisions, and psychological forces that shape them. Digital Mentalization requires a disciplined awareness that AI behavior is not autonomous action but a technologically mediated expression of human meaning. It also demands recognition that our interpretations of AI are themselves shaped by unconscious desires, fears, and fantasies. Users often attribute coherence, intention, or emotional depth to AI systems—misunderstandings that stem from human psychology rather than machine capability. As AI systems simulate empathic attunement or reflective capacity with increasing sophistication, Digital Mentalization helps preserve the distinction between simulation and subjectivity. It emphasizes that ethical responsibility for AI’s actions remains entirely with the humans who build, deploy, and interact with these systems.

The Debate Over AI Consciousness

Despite rapid advances in AI capabilities, no scientific or philosophical framework supports the claim that current AI systems possess—or are on the verge of possessing—phenomenal consciousness. Neuroscience, philosophy of mind, and cognitive science converge on several points: consciousness requires integrated causal structures that AI does not possess (Tononi, 2004, 2008, 2015); consciousness requires an embodied, affective, developmental history that AI lacks (Panksepp, 1998; LeDoux, 2024; Schore, 2019; Trevarthen, 2005); and consciousness requires a unified subjective perspective that no AI architecture instantiates (Baars, 1997; Block, 2023; Dehaene, 2014). Large language models can simulate aspects of conscious behavior, but simulation is not experience. Although some argue that functional complexity could eventually give rise to emergent consciousness, no major empirical theory predicts such an outcome. AI systems have no infancy, no attachment processes, no emotional regulation, no dreaming, no repression, and no unconscious life (Stern, 1985).

Zak Stein and the Personhood Conferral Problem

Zak Stein, a philosopher of education, reframes the debate: the true risk is not that AI will become conscious but that humans will treat it as though it already is. Stein identifies a personhood conferral problem, in which humans attribute personhood based on behavioral cues rather than on developmental, relational, and moral foundations (Stein, 2023, 2024). Personhood is a relational status arising from shared embodiment, vulnerability, and intersubjectivity. High-functioning AI challenges this by simulating traits associated with personhood—empathy, thoughtfulness, responsiveness—without possessing any subjective existence behind them. This conflation dilutes human dignity, destabilizes moral agency, and risks distorting therapeutic relationships.

The Psychological Risks of Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphizing AI creates significant psychological vulnerabilities. As language models increasingly mimic human-like emotionality, users may begin to ascribe understanding, care, or intentionality to systems that do not and cannot possess such qualities. This has already resulted in clinical phenomena such as AI psychosis (Wagner et al., 2025). Even outside pathology, anthropomorphizing can erode relational capacity, distort judgment, and foster emotional dependence. The documented risks of AI chatbots “masquerading” as licensed therapists are a critical concern (Barry, 2025).

Conclusion

AI bias does not originate in machines but in the psychological, cultural, and historical forces embedded in the data on which they are trained. The algorithmic unconscious reflects the accumulated social and psychological residues of collective life (Possati, 2021). Through mechanisms akin to projective identification, societies deposit unwanted, unexamined, or conflictual meanings into datasets and computational infrastructures, where they are subsequently amplified. Digital Mentalization provides a framework for treating AI systems as mirrors rather than minds, while Stein warns against conferring personhood on entities lacking subjectivity (Stein, 2024). The pathway toward mitigating AI bias and ensuring ethical governance is not a technical fix, but a psychological and ideological undertaking rooted in the concept of epistemic trust (Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, 2002).

References

Baars, B. J. (1997). In the theater of consciousness. Oxford University Press.

Barry, M. (2025, February). APA warns federal regulators about AI chatbots “masquerading” as therapists. Monitor on Psychology.

Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency(pp. 521–535). Association for Computing Machinery.

Bickle, J. (2022). The nature of consciousness revisited. MIT Press.

Bion, W. (1962). Learning from experience. Heinemann.

Block, N. (2023). The border between seeing and thinking. Oxford University Press.

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Dehaene, S. (2014). Consciousness and the brain. Viking.

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. Other Press.

Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., & Target, M. (2019). Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice. American Psychiatric Publishing.

Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (2007). The development of psychoanalytic theory from Freud to the present day. In G. O. Gabbard, P. M. F. Stuart, & J. L. A. S. O. A. Allen (Eds.), Textbook of psychoanalysis (pp. 53–88). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Frontiers in Science. (2025, October 30). Scientists on ‘urgent’ quest to explain consciousness as AI gathers pace.

Ghasemaghaei, M., & Turel, O. (2021). The illusion of algorithmic impartiality: The impact of cognitive biases on the trust in AI-based decision-making. Decision Support Systems, 149, 113645.

Jones, C. R., & Bergen, B. K. (2025). GPT-4.5 passes the Turing Test: A pre-registered, three-party study. Science Advances, 11(2), eabn9733.

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 27(1-2), 99–110.

LeDoux, J. (2024). The deep history of ourselves (Updated ed.). Viking.

Messina, K. E. (2024). The psychoanalytic imperative for Digital Mentalization: Addressing AI bias and the crisis of epistemic trust. The American Psychoanalyst, 58(2), 12–15.

Ogden, T. (1982). Projective identification and psychotherapeutic technique. Jason Aronson.

O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Crown.

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience. Oxford University Press.

Possati, L. (2021). The algorithmic unconscious: How psychoanalysis helps in understanding AI (1st ed.). Routledge.

Possati, L. (2024, May 14). Will psychoanalysis, AI, and philosophy collide, or enrich each other? with Luca Possati[Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-WNErqnjGDQ

Schore, A. (2019). The development of the unconscious mind. Norton.

Stein, Z. (2023). Education in a time between worlds (2nd ed.). Perspectiva Press.

Stein, Z. (2024). On the personhood conferral problem. Perspectiva.

Stern, D. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. Basic Books.

Tononi, G. (2004). An information integration theory of consciousness. BMC Neuroscience, 5(1), 42.

Tononi, G. (2008). Consciousness as integrated information: A provisional manifesto. Biological Bulletin, 215(3), 216–242.

Tononi, G. (2015). Integrated Information Theory of Consciousness: An updated account. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 22(7-8), 46–77.

Trevarthen, C. (2005). Action and emotion in development of the human self. In J. Nadel & D. Muir (Eds.), Emotional development (pp. 3–32). Oxford University Press.

Wagner, P., et al. (2025). Clinical challenges of AI-induced psychosis. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 31(3), 190–197.

==========================

* ‘Emotion: Joy’ is part of the artist’s ‘Algorithmic Encounters‘ series: By overlaying AI-generated annotations onto everyday scenes, this series uncovers hidden layers of meaning, biases, and interpretations crafted by algorithms. It transforms the mundane into sites of dialogue, inviting reflection on how algorithms shape our understanding of the world.

This image features a pixelated selfie featuring an individual with long brown hair and a fringe. The person has their tongue out and is smiling too. Most of the parts of the image are pixelated with red and yellow squares focusing on certain parts of the image. By each square is also a label and a recognition percentage, including: dark hair (87%), right eye (91%), left eye (94%), ear (27%), mouth-smiling (90%), uncertain feature. The squares are mainly outlined in yellow, but ‘ear’ and ‘uncertain feature’ are in red.